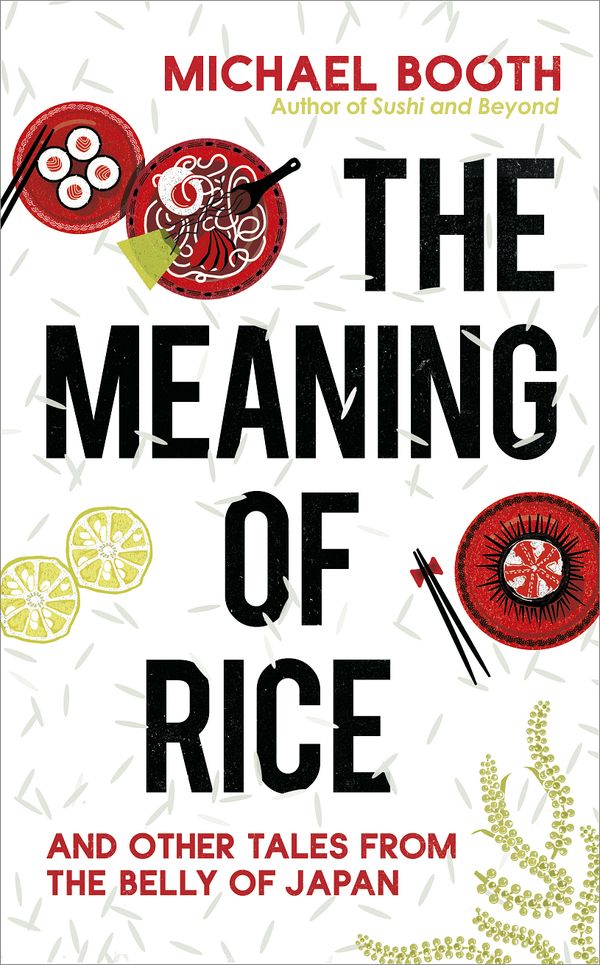

A must read for any lover of Japanese food and culture, in The Meaning of Rice: And Other Tales from the Belly Of Japan, award-winning writer Michael Booth embarks on a journey across Japan with his family to explore the country’s incredible gastronomic scene, from ramen to sushi. Meticulously researched and humorous throughout, The Meaning of Rice introduces readers to Japanese food heroes, secret histories and upcoming trends from this fascinating country. The following is an extract from this brilliant book to give you a flavour of what a fantastic read it is for any foodie.

You can get your copy of The Meaning of Rice here.

I hoped finally to understand the meaning of rice to the Japanese. For many years, in fact since I first travelled to Japan, there has been an elephant in the room in terms of my understanding of Japanese food, and that elephant is rice. I knew how important rice is to the Japanese; it is perhaps the single most significant ingredient, not just in Japanese cuisine, but also as an elemental part of Japanese culture. After all, ‘gohan’, the word for cooked rice, also means ‘meal’. I knew that every proper Japanese meal should finish with a bowl of steamed white rice. I knew that one shouldn’t leave one’s chopsticks sticking out of a bowl of rice because this is a symbol of death, and that it is frowned upon to leave any rice in the bowl at the end of the meal. Having asked innumerable Japanese what their favourite meal is, or what they would choose as their last meal, I also knew that ‘just a bowl of rice’ was the most common answer to both questions. But I also knew that, personally, I found plain steamed white rice deeply uninteresting. I usually left my bowl at the end of meals in Japan, enduring the slightly pained expressions of my fellow diners as I did so.

Earlier, while interviewing the Osakan Michelin-starred chef Fujiwara, he had referenced legendary Kyoto restaurant Sojiki Nakahigashi, one of the most difficult places in the city at which to make a reservation, and where the lunch menu can sometimes be entirely focused on rice. The chef, Hisao Nakahigashi, one of Fujiwara’s mentors, is an influential figure in Japanese cuisine, but unknown beyond Japan. When I had met him, Nakahigashi, a handsome man in his mid-sixties, was affable enough yet I sensed within him an iron core. He has owned his restaurant, close to the Ginkaku-ji temple, for twenty years and every day he forages in the mountains surrounding Kyoto for many of the plants and vegetables he uses. He served me his four-course rice menu for lunch one time when I visited with a Japanese TV crew for a documentary. The meal started with ‘niebana’, deliberately undercooked rice served straight from the donabe, the traditional earthenware pot in which it was cooked in front of us, using water from a well in the restaurant’s backyard. This rice, organic and sun-dried from Yamagata Prefecture, north of Niigata, reappeared in the second course alongside some himono, salted, sun-dried, then grilled fish. In the third course, ‘okoge’, the rice was deliberately browned, making it nice and crusty (it is a universal truth that everyone, no matter their race, creed or colour, likes the browned, crusty rice in the bottom of the pan best of all), before taking a final bow floating in a bowl of hot water with ume and perilla. It was an ascetic, thought-provoking experience, and unquestionably the best rice I had eaten up until that point, but it was still, you know, just rice. While expressing my – sincere – enjoyment about the lunch for the cameras, there remained the nagging sense that I had missed something.

White rice contains little of nutritional value; all the vitamins and minerals are in the husk, which is removed to make it look white, so why eat it, other than to fill a hole which I would much rather fill with dessert? For the last three decades in the West we have been told that brown rice is the thing to eat if we want the healthy rice option, and I have done, even though it tastes like the bits our pet rabbit leaves behind at the bottom of his bowl. A diet based on the consumption of white rice was, let’s not forget, the reason the Japanese sailors suffered from beriberi back in the nineteenth century. To my taste buds it didn’t have much by way of flavour, either. And I also knew that more and more Japanese were coming to a similar conclusion; consumption in Japan has halved since the early sixties. This is normal: a decline in rice consumption invariably coincides with an increase in a country’s GDP: the richer people get, the less rice they eat. Today, the Japanese currently rank a lowly fiftieth globally in terms of per capita rice consumption. Rice was, then, yet another of those traditional food products which younger Japanese people appeared to be rejecting, along with tofu and tsukudani, funa zushi, homemade dashi and sake.

This is why there was no rice-themed chapter in my first Japan book all those years ago. I knew at the time I should investigate it but the subject neither interested me, nor could I find a way into it, a story to tell about rice. Until, that is, I met Furukawa-san for the first time, which had happened seven months earlier, prior to me and my sons turning up in his fields to help with the planting.

I wasn’t sure what to expect of my first trip to Fukushima Prefecture. Of course, I had seen the footage of the devastation wreaked by the tsunami in 2011 but Furukawa’s farm was about fifty miles away from the coast, so presumably it had been protected from the flooding. Of course, I did ponder the consequences of any air-, water-, or land-borne nuclear contamination. After the tsunami, I know some expats in Tokyo had reacted by leaving the city for ever. One prominent Japanese food figure of my acquaintance had bought two different types of Geiger counter for use in his home in Tokyo; other Japanese people I asked admitted they had immediately stopped buying anything grown in Fukushima. Despite the assurances from the Japanese government that all produce was being screened for radioactive contamination, many had switched to sourcing their food from the western part of Japan, or overseas. (Oddly, whenever I asked these people about eating fish caught in Japanese waters, they expressed no reservations. ‘It’s OK, they are not fishing off the coast of Fukushima,’ I was assured. ‘But fish swim, right?’ I would think to myself. The bonito, or katsuo, for instance, migrates hundreds of miles up and down the Japanese coast each year. What was to stop contaminated fish from making their way down the coast to be caught off Shizuoka, for instance? But the conversation would usually mysteriously change at this point, and we would all tuck into our sashimi.)

Arriving back in November 2015 to spend a couple of days filming in Furukawa’s fields for the intro to that NHK New Year’s special episode, the city of Koriyama appeared unaffected by the 2011 disaster, at least physically. Small and low-rise by the standards of most Japanese cities, it had a slight Back to the Future feel, as if all development had halted around about 1988.

My first meeting with Furukawa-san, dressed in his regulation outfit of blue overalls and a John Deere cap, was staged and repeated a couple of times for the cameras: I disembarked from a taxi and strode over to meet him as he cut some rice stalks with a small scythe (we were visiting towards the end of the harvest time). Despite the artifice of the situation, I was immediately taken by his unaffected welcome to me and the crew. Furukawa’s broad, suntanned face fell naturally to a relaxed smile. He was fifty-eight years old and had been a farmer for forty of them, but looked ten years younger. Though he was busy finishing the harvest, he was patient as we repeated our conversations, again for the cameras, and I ‘helped’ with various tasks in the fields. Over the course of the day I was filmed cutting the rice stalks with a scythe, and stacking them in bundles up against thick, tall wooden poles to dry in the sun, in a traditional manner these days rarely seen in the Japanese countryside.

We broke for lunch. It was finally time for me to taste Furukawa’s rice. His daughter-in-law had prepared some onigiri – fist-sized clumps of rice pressed together in a triangular shape, and wrapped with a sheet of nori, usually with a small piece of something savoury in the middle of the onigiri – tinned salmon, konbu tsukudani, ume, or pickled Japanese plums. The onigiri rice grains glinted in the sun. They seemed to radiate their own light source. I took a self-conscious bite, watched by a dozen people and two cameras. The rice had a lovely, lingering sweet mineral flavour but I was failing abjectly to summon some kind of transcendent revelation, some ‘aha’ moment in which I suddenly understood why steamed white rice resonated so powerfully within the Japanese soul. It was just very, very nice rice. Excellent rice. The best rice I had ever eaten, for sure, but still rice. The homemade pickled ume I was also offered, on the other hand, were much more interesting. Rather embarrassingly, my reaction was far more demonstrative when I ate the plums than when I ate Furukawa’s rice. Oh dear. We returned to the harvesting and conversation. I noticed his fields were full of insects – spiders, crickets, weird alien flying things – as well as frogs and lizards. He explained that most of his paddies were fully biodynamic. ‘There is no point in fighting nature, so I just leave it to the power of the soil,’ he said.